Tom Sponheim (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Tom Sponheim (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{GoogleTranslateLinks}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SODIS_and_CooKit_pasteurizer.jpg|thumb|left|SODIS experiments by Dr. [[Bob Metcalf]] using common plastic bottles (on left) were mostly successful, but small amounts of E. coli survived.]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==SODIS== |

||

| ⚫ | A possible alternative to [[Water pasteurization|water pasteurization]] is '''SODIS''' or ''solar water disinfection''. This method seeks to inactivate microbes in contaminated water -- exposing transparent bottles of water, placed horizontally on a flat surface, to direct sunshine for five to six hours -- was first reported in 1980 by Aftim Acra et al. at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. UNICEF published a booklet describing this method in 1984. This procedure has been developed by the Swiss Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). If possible, Eawag recommends placing the clear bottle on a metal surface, e.g. a corrugated metal roof, to enhance heating and increase microbe inactivation (see [http://www.sodis.ch http://www.sodis.ch]). |

||

The SODIS procedure will reliably inactivate bacteria on sunny days. Bacteria concentrations for most pathogenic organisms can be expected to drop by 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1'000-10'000) even if the method is applied by an relatively unskilled person in the field (Sobsey M.D., Stauber C.E., Casanova L.M., Brown J.M., Elliott M.A. (2008). Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World. Environ. Sci. Technol., ASAP Article, 10.1021/es702746n). |

The SODIS procedure will reliably inactivate bacteria on sunny days. Bacteria concentrations for most pathogenic organisms can be expected to drop by 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1'000-10'000) even if the method is applied by an relatively unskilled person in the field (Sobsey M.D., Stauber C.E., Casanova L.M., Brown J.M., Elliott M.A. (2008). Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World. Environ. Sci. Technol., ASAP Article, 10.1021/es702746n). |

||

| Line 17: | Line 23: | ||

Furthermore, the SODIS method suffers because it has no certain end-point to decide when the water is safe for consumption. Therefore, Eawag recommends to expose water for two consecutive days if there is only limited sun, and to filter turbid water before applying SODIS. |

Furthermore, the SODIS method suffers because it has no certain end-point to decide when the water is safe for consumption. Therefore, Eawag recommends to expose water for two consecutive days if there is only limited sun, and to filter turbid water before applying SODIS. |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Spade_WAPI.jpg|thumb|300px|[[SPADE]] [[WAPI]]]] |

||

| + | The efficacy of the SODIS approach has been discussed in this article. While exposure to sunlight kills many forms of contamination in the water, a more effective technique is to pasteurize the water. An important aspect to pasteurization is that it allows for the use of a [[WAPI]], a simple device to indicate when the water has reached a safe temperature. When the water reaches 65°C(150°F) it is suitable for drinking. Several designs use a melting wax method. A recent version, called the [[SPADE]], is designed to be fitted directly to the cap on a water bottle. After drilling a 1/4" hole through the cap. The slender clear tube, with wax at one end, is submerged into the bottle. Reaching a safe temperature, the wax runs to the bottom of the tube. A compact approach to providing water pasteurization using bottles, similar to the SODIS approach, but also with a simple device to indicate the water's safety for drinking. |

||

Comment by anonymous reader: |

Comment by anonymous reader: |

||

| Line 22: | Line 31: | ||

Eawag (the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology has been involved in research on different aspects of solar water disinfection. I agree with you that boiling is the only household water treatment method that can produce completely sterile water (i.e. kill all microorganisms). While not producing sterile water, SODIS, chlorination and different types of filters are effective in removing diarrhea causing microorganisms. The technical disinfection efficiency of these technologies is in the range of 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1000-10000) on average, with filters performing better for larger protozoa, and SODIS and chlorination perform better for viruses. The statement you added that "SODIS is not nearly as reliable as [boiling or] chlorination" is not supported by the literature (see, e.g. review articles by Sobsey 2008: Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World, Environmental Science & Technology; Clasen 2007: Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries, Journal of Water and Health). There are differences between the mentioned technologies in terms of the availability of materials and convenience for the users that may render one method preferable over others in a certain situation; in terms of disinfection efficiency, however, they all perform reliably well. Also note that safe storage is a critical aspect in this context. Studies on boiling (e.g. Clasen 2008: Microbiological Effectiveness and Cost of Disinfecting Water by Boiling in Semi-urban India, Am J Trop Med Hyg.) have shown that a very high percentage of households where boiling is used for drinking water treatment, people consumed polluted water due to re-contamination during storage of the water after boiling. SODIS bottles and chlorination (if the correct dose of chlorine is applied) provide safe storage of the treated water. |

Eawag (the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology has been involved in research on different aspects of solar water disinfection. I agree with you that boiling is the only household water treatment method that can produce completely sterile water (i.e. kill all microorganisms). While not producing sterile water, SODIS, chlorination and different types of filters are effective in removing diarrhea causing microorganisms. The technical disinfection efficiency of these technologies is in the range of 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1000-10000) on average, with filters performing better for larger protozoa, and SODIS and chlorination perform better for viruses. The statement you added that "SODIS is not nearly as reliable as [boiling or] chlorination" is not supported by the literature (see, e.g. review articles by Sobsey 2008: Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World, Environmental Science & Technology; Clasen 2007: Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries, Journal of Water and Health). There are differences between the mentioned technologies in terms of the availability of materials and convenience for the users that may render one method preferable over others in a certain situation; in terms of disinfection efficiency, however, they all perform reliably well. Also note that safe storage is a critical aspect in this context. Studies on boiling (e.g. Clasen 2008: Microbiological Effectiveness and Cost of Disinfecting Water by Boiling in Semi-urban India, Am J Trop Med Hyg.) have shown that a very high percentage of households where boiling is used for drinking water treatment, people consumed polluted water due to re-contamination during storage of the water after boiling. SODIS bottles and chlorination (if the correct dose of chlorine is applied) provide safe storage of the treated water. |

||

| − | In the light of this information, SODIS is not inferior to boiling and chlorination (nor superior, the user's choice will depend on the local circumstances and personal preferences). |

+ | In the light of this information, SODIS is not inferior to boiling and chlorination (nor superior, the user's choice will depend on the local circumstances and personal preferences). |

| + | Potentially, there appears to be a health risk associated with reusing plastic bottles when disinfecting water for potable use. According to [[Matthew Rollins]], evidence has shown there is a release of cancer causing chemicals when plastic bottles are placed in direct sunlight for extended periods. Glass containers, while more vulnerable to breakage, may be a preferable alternative. |

||

| − | + | ==See also== |

|

| + | * [[WAPI]] |

||

| − | |||

* [[Water pasteurization]] |

* [[Water pasteurization]] |

||

* [[Media:Sodis_Aristanti.pdf|Solar Water Disinfection: Water Quality Improvement at Household Level with Solar Energy]] |

* [[Media:Sodis_Aristanti.pdf|Solar Water Disinfection: Water Quality Improvement at Household Level with Solar Energy]] |

||

* [[Solvatten]] - A device that makes synergistic use of UV light and heat gain |

* [[Solvatten]] - A device that makes synergistic use of UV light and heat gain |

||

| + | * [[Solar puddle]] |

||

| − | + | ==External links== |

|

| + | *'''May 2010:''' [http://www.wpi.edu/Pubs/ETD/Available/etd-0423103-124244/unrestricted/rojko.pdf Solar Disinfection of Drinking Water] - ''Christine Rojko '' |

||

| − | |||

| + | *'''May 2010:''' [http://www.cdc.gov/safewater/publications_pages/options-sodis.pdf Household Water Treatment Options in Developing Countries:Solar Disinfection (SODIS)] - ''CDC January 2008'' |

||

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SODIS Wikipedia article on SODIS] |

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SODIS Wikipedia article on SODIS] |

||

*[http://www.sodis.ch/ Solar Water Disinfection] - ''EAWAG'' |

*[http://www.sodis.ch/ Solar Water Disinfection] - ''EAWAG'' |

||

| Line 38: | Line 50: | ||

*[http://www.hip.watsan.net/content/download/2435/13792/file/HWTS%20Option-SODIS.pdf USAID / Health Improvement Project] |

*[http://www.hip.watsan.net/content/download/2435/13792/file/HWTS%20Option-SODIS.pdf USAID / Health Improvement Project] |

||

*[http://www.cawst.org/index.php?id=132#SODIS Centre for Affordable Water and Sanitation Technology] |

*[http://www.cawst.org/index.php?id=132#SODIS Centre for Affordable Water and Sanitation Technology] |

||

| + | *'''August 2009:''' [http://vietnamnews.vnagency.com.vn/showarticle.php?num=02SOC170809 Solar rays help purify drinking water], by Khanh Van, ''Viet Nam News'' |

||

*'''June 2008:''' [http://www.cnn.com/video/?/video/world/2008/07/01/mckenzie.gg.kenya.sun.water.cnn Kenya's sun water] - ''CNN'' |

*'''June 2008:''' [http://www.cnn.com/video/?/video/world/2008/07/01/mckenzie.gg.kenya.sun.water.cnn Kenya's sun water] - ''CNN'' |

||

*'''April 2008:''' [http://www.womensenews.org/article.cfm/dyn/aid/3560/context/archive Kenyans Tap Sun to Make Dirty Water Sparkle] - ''Women's eNews'' |

*'''April 2008:''' [http://www.womensenews.org/article.cfm/dyn/aid/3560/context/archive Kenyans Tap Sun to Make Dirty Water Sparkle] - ''Women's eNews'' |

||

Revision as of 01:48, 29 January 2015

SODIS experiments by Dr. Bob Metcalf using common plastic bottles (on left) were mostly successful, but small amounts of E. coli survived.

SODIS

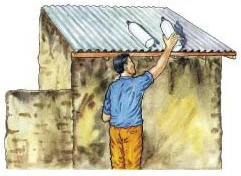

A possible alternative to water pasteurization is SODIS or solar water disinfection. This method seeks to inactivate microbes in contaminated water -- exposing transparent bottles of water, placed horizontally on a flat surface, to direct sunshine for five to six hours -- was first reported in 1980 by Aftim Acra et al. at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. UNICEF published a booklet describing this method in 1984. This procedure has been developed by the Swiss Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). If possible, Eawag recommends placing the clear bottle on a metal surface, e.g. a corrugated metal roof, to enhance heating and increase microbe inactivation (see http://www.sodis.ch).

The SODIS procedure will reliably inactivate bacteria on sunny days. Bacteria concentrations for most pathogenic organisms can be expected to drop by 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1'000-10'000) even if the method is applied by an relatively unskilled person in the field (Sobsey M.D., Stauber C.E., Casanova L.M., Brown J.M., Elliott M.A. (2008). Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World. Environ. Sci. Technol., ASAP Article, 10.1021/es702746n).

SODIS is promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), and others thoughout the third world, as a viable treatment for disinfecting drinking water and reducing the incidence of waterborne diseases. Health workers stress that boilling, or chemical treatment like chlorination, is much preferred over SODIS, since boiling is 100 percent reliable at killing pathogens, and chemical treatment is close to 100 percent reliable except for hard- to-kill pathogens like Cryptosporidium. SODIS is not nearly as reliable as boiling or chlorination, but since boiling requires fuel or other resources that are often in short supply in third worlds locations, SODIS is promoted as being far better than drinking untreated water.

Despite the extensive research on the effectiveness of SODIS in removing pathogens from drinking water in both lab and field conditions (see, e.g., the scientific articles listed here: http://www.sodis.ch/Text2002/T-Research.htm), some anectotal accounts report lower disinfection efficiencies (which could be caused by incorrect application of the method among other reasons).

In the summer of 2002 Christine Polinelli, from the Australian Department of Health, joined Dr. Metcalf in Meatu district of Tanzania to test CooKit water pasteurization, and the SODIS method, with the naturally contaminated water delivered to their guesthouse. This water had between 10-100 E. coli bacteria per milliliter. (The WHO considers water to be heavily contaminated if it has one E. coli per milliliter.) Water heated in a two-liter black metal container in a CooKit was free of E. coli within two hours, when temperatures reached 60°C. Water from the same source was given the SODIS treatment in the 1.5-liter blue-tinted plastic bottles available in Tanzania. Although we obtained over 90 percent inactivation of E. coli in 5-6 hours, viable E. coli were still sometimes present in one milliliter and ten milliliter samples. The moderate turbidity of the river water may have contributed somewhat to protecting E. coli.

Trish Morrow reports: Earlier in the year (2007), on 25 August, engineering staff tested the SODIS method of water treatment. Four bottles of contaminated water were collected from the same location on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. One bottle was painted black with blackboard paint, two bottles were left clear and one bottle was half painted with blackboard paint, the other half being clear. Three bottles were placed in the sun for approximately four hours and the fourth bottle (clear, not painted) was kept in the shade indoors during the entire time. The bottles were placed on the corrugated iron roof of our office, where they were in a nearly horizontal position. The half-black bottle was placed with the transparent side upwards. After the three bottles had been left in the sun for approximately four hours, all four samples were analysed using a Del Agua bacteriological test kit. This kit uses the membrane filtration method. Results were as follows: Transparent bottle left in sun had 11 fecal coliforms per 100ml, bottle painted black had 2 fecal coliforms per 100ml, the control (raw water from Lake Tanganyika) had 29 fecal coliforms per 100ml and the bottle which was half painted black had 0 fecal coliforms.

Dr. Bob Metcalf and his students have found that viruses are more resistant to direct sunshine than are bacteria. Research conducted by Negar Safapour and myself, using a bacterial virus, supports this (see paper in Applied and Environmental Microbiology Vol. 65, #2, pp859-861, 1999; available online at: http://aem.asm.org). Another student, Yen Cao Verhoeven, studied the effects of the SODIS method on rotaviruses, with similar results. Her findings were presented as a poster at the American Society for Microbiology annual meeting in May 2000. Sobsey et al. specify the reduction of concentrations of viruses by SODIS as being in the range of 2 orders of magnitude (factor 100) under field conditions and 4 orders of magnitude (factor 10'000) under controlled conditions. Protozoa are particularly resistant, and the complete inactivation of spores or cysts requires high temperatures of 50 degrees or higher.

The SODIS method cannot be used for turbid water or for milk, since turbidity and non-clear liquids reduce solar radiation intensity. Furthermore, SODIS does not remove chemical pollutants if present in the water. Bottles need to be available for the process in sufficient quantity, which can be a limiting factor in very remote areas.

Furthermore, the SODIS method suffers because it has no certain end-point to decide when the water is safe for consumption. Therefore, Eawag recommends to expose water for two consecutive days if there is only limited sun, and to filter turbid water before applying SODIS.

SPADE WAPI

The efficacy of the SODIS approach has been discussed in this article. While exposure to sunlight kills many forms of contamination in the water, a more effective technique is to pasteurize the water. An important aspect to pasteurization is that it allows for the use of a WAPI, a simple device to indicate when the water has reached a safe temperature. When the water reaches 65°C(150°F) it is suitable for drinking. Several designs use a melting wax method. A recent version, called the SPADE, is designed to be fitted directly to the cap on a water bottle. After drilling a 1/4" hole through the cap. The slender clear tube, with wax at one end, is submerged into the bottle. Reaching a safe temperature, the wax runs to the bottom of the tube. A compact approach to providing water pasteurization using bottles, similar to the SODIS approach, but also with a simple device to indicate the water's safety for drinking.

Comment by anonymous reader:

Eawag (the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology has been involved in research on different aspects of solar water disinfection. I agree with you that boiling is the only household water treatment method that can produce completely sterile water (i.e. kill all microorganisms). While not producing sterile water, SODIS, chlorination and different types of filters are effective in removing diarrhea causing microorganisms. The technical disinfection efficiency of these technologies is in the range of 3-4 orders of magnitude (factor 1000-10000) on average, with filters performing better for larger protozoa, and SODIS and chlorination perform better for viruses. The statement you added that "SODIS is not nearly as reliable as [boiling or] chlorination" is not supported by the literature (see, e.g. review articles by Sobsey 2008: Point of Use Household Drinking Water Filtration: A Practical, Effective Solution for Providing Sustained Access to Safe Drinking Water in the Developing World, Environmental Science & Technology; Clasen 2007: Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries, Journal of Water and Health). There are differences between the mentioned technologies in terms of the availability of materials and convenience for the users that may render one method preferable over others in a certain situation; in terms of disinfection efficiency, however, they all perform reliably well. Also note that safe storage is a critical aspect in this context. Studies on boiling (e.g. Clasen 2008: Microbiological Effectiveness and Cost of Disinfecting Water by Boiling in Semi-urban India, Am J Trop Med Hyg.) have shown that a very high percentage of households where boiling is used for drinking water treatment, people consumed polluted water due to re-contamination during storage of the water after boiling. SODIS bottles and chlorination (if the correct dose of chlorine is applied) provide safe storage of the treated water.

In the light of this information, SODIS is not inferior to boiling and chlorination (nor superior, the user's choice will depend on the local circumstances and personal preferences).

Potentially, there appears to be a health risk associated with reusing plastic bottles when disinfecting water for potable use. According to Matthew Rollins, evidence has shown there is a release of cancer causing chemicals when plastic bottles are placed in direct sunlight for extended periods. Glass containers, while more vulnerable to breakage, may be a preferable alternative.

See also

- WAPI

- Water pasteurization

- Solar Water Disinfection: Water Quality Improvement at Household Level with Solar Energy

- Solvatten - A device that makes synergistic use of UV light and heat gain

- Solar puddle

External links

- May 2010: Solar Disinfection of Drinking Water - Christine Rojko

- May 2010: Household Water Treatment Options in Developing Countries:Solar Disinfection (SODIS) - CDC January 2008

- Wikipedia article on SODIS

- Solar Water Disinfection - EAWAG

- WHO Network for Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage

- USAID / Health Improvement Project

- Centre for Affordable Water and Sanitation Technology

- August 2009: Solar rays help purify drinking water, by Khanh Van, Viet Nam News

- June 2008: Kenya's sun water - CNN

- April 2008: Kenyans Tap Sun to Make Dirty Water Sparkle - Women's eNews

- Water Disinfection by Solar Radiation

- Test results from Brazil

- Información SODIS