Patricia McArdle's novel was inspired by the year she spent in northern Afghanistan.

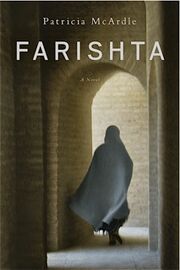

The novel, Farishta, by Solar Cookers International Board Member Patricia McArdle tells the compelling story of diplomat Angela Morgan. Stationed at a remote British Army outpost in northern Afghanistan, Angela becomes frustrated at her inability to contribute to the country’s reconstruction. Slipping away disguised in a burka to provide aid to refugees, Angela becomes their farishta—or "angel" in the local Dari language—and discovers a new purpose for her life. Farishta draws on the author’s experience as a diplomat in Afghanistan and her commitment to solar cooking. The importance and practicality of solar cooking is woven into the novel as Angela shares it with the local population.Patricia McArdle is a retired Foreign Service officer who has served in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe, it was McArdle's final posting in northern Afghanistan that served as her great inspiration. In her words, "... I also drew on the experiences of other female foreign services officers and journalists that I met or heard about while I was in Afghanistan." One story in the novel was inspired by an experience McArdle had while on patrol with British soldiers. In very remote areas, McArdle noticed groups of Afghan children dragging large bundles of kindling back to their homes in the blistering heat — and it got her thinking: "I remembered that I had built a solar cooker when I was a Girl Scout many years ago," McArdle explains. "I wondered if the Afghans knew about solar cooking because they had all this sun and they have no wood." McArdle searched online, and found instructions for building cookers on a site called Solar Cookers International. "The people were fascinated," she says. The story not only appears in the novel, but McArdle now sits on the board of directors of SCI.

Not all of McArdle's experiences ended so positively and she hopes her book will draw attention to some of the issues — such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder — facing soldiers and Foreign Service officers. While she was never the victim of any direct attacks, the experience of living in a combat zone affected her long after she returned home. "I was afraid to take my dog outside at night for a walk," she admits. McArdle doesn't believe she experienced PTSD, but she says it got her thinking: "What about people, civilians and soldiers who had experienced this? It's quite horrifying because it's all inside, nobody can see it, and you can't explain it to anyone."

In Farishta, McArdle also addresses what she views as the misallocation of American resources. "I really think that in a country like Afghanistan we should be focused much more on sustainable reconstruction," she says. McArdle cites a 2004 Department of Energy report which shows that Afghanistan has abundant natural resources that could be developed. Instead of importing American building and farming techniques, McArdle feels that the U.S. should be working with locals and taking advantage of practices that have been employed in the country for thousands of years. "Afghan farmers are the ultimate locavores," she says. "They grow their own crops, they have very little arable land and they take very good care of it. We should be helping them with organic techniques ... instead of bringing fertilizers and seeds that they'll have to replace."

- text borrowed from http://www.npr.org

Excerpt: 'Farishta', by Patricia McArdle, Riverhead Hardcover, publisher

The first ring jarred me awake seconds before my forehead hit the keyboard. I inched slowly back in my chair, hoping no one had noticed me dozing off. Narrowing my eyes against the flat glare of the ceiling lights, I scanned the long row of cubicles behind me. I was alone. The second ring and the scent of microwave popcorn drifting in from a nearby office reminded me I was supposed to meet some colleagues for din ner and a movie near Dupont Circle at eight. It was almost seven thirty. The third ring froze me in place when I saw the name flashing on the caller ID.

If irrational fear could still paralyze me like this after all these years, then perhaps it really was time to give up. It wasn't only real danger that would accelerate my pulse and cause me to stop breathing like a frightened rabbit staring down the barrel of a shotgun. It was little things. Tonight it was a telephone call. I forced myself to grab the receiver halfway through ring number four. "This is Angela Morgan," I said, struggling to suppress the anxiety that had formed a painful knot in my throat. My computer beeped and coughed up two messages from the U.S. Em bassy in Honduras. I ignored them and began taking slow, measured breaths. "Angela, you're working late tonight. It's Marty Angstrom from personnel."

Marty's chirpy, nasal voice resonated like the slow graze of a fork down an empty plate. He was stammering, obviously surprised that anyone in the Central American division at the State Department would pick up the phone this late on a Friday evening. I had apparently upset his plan to leave a voice message that I wouldn't hear until Monday morning. "Hello, Marty. It's been a long time." My heart was thundering. "Is this a good news or a bad news call?" "It depends," said Marty. "On what?" "On what your definition of good is." He chuckled.

The wish list I'd submitted to personnel for my next overseas diplomatic posting had been, in order of preference: London, Madrid, Nairobi, San Salvador, Lima, Caracas, Riga, St. Petersburg, and Kabul. I'd thrown in Kabul at the last minute, thinking it would demonstrate that I was a team player and increase my chances for the London assignment. But they would never send me to Kabul, not after what had happened in Beirut. "Marty, please get to the point. Did I get London?" I could hear him breathing through his nose into the phone like an old man with asthma. He sounded almost as nervous as I felt. Not a good sign. Was I being sent south of the border again just because I spoke Spanish? But why would that make Marty nervous?

Before I retired or was forced out of the Foreign Service for not getting promoted fast enough, I was hoping for just one tour of duty in Western Europe. Foreign Service Officers, like military officers, must compete against their colleagues of similar rank for the limited number of promotions available each year. Consistently low performers are drummed out long before reaching the traditional retirement age of sixty-five.

I desperately wanted an assignment in London, but I'd settle for Madrid. After all I'd been through — I deserved it. "Well, you'll be spending a lot of time with the Brits," Marty replied eagerly. "Meaning?" I put him on speaker and began to rearrange the stacks of papers on my desk. My pulse and breathing were returning to normal. "Listen, Angela, I know you had some tough times a while back, but that was more than two decades ago."

Tough times — a dead husband and a bloody miscarriage. Yeah, those were definitely tough times, I thought, looking over at the small silver-framed photo of Tom and me. We were sitting on our bay Arabian geldings at the Kat touah stables near Beirut. Our knees were touching. His horse was nuzzling mine. We were laughing. Tom and I had met for the first time in 1979 at a private stable in the Virginia hunt country, where we'd arrived separately to rent horses for a few hours on the weekend. Although we were both studying Farsi in prepa ration for our first assignments as junior diplomats to the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, we had different instructors at the Foreign Service Institute. Our paths had never crossed until that warm summer morning, when the New Mexico rancher's daughter and the southern prep school boy discovered the first of their many common interests.

"Ange, you're going to get kicked out of the Foreign Service in another year if you don't get promoted," warned Marty. That was true. After the embassy bombing killed Tom, and I lost the baby a few days later, the Department had ordered me back to the United States to recover, but not for long. I stayed with my parents for three months, was given a low-stress desk job in D.C. for the following year, and was then expected to start Russian language training and take the assignment in Len ingrad where Tom and I should have gone together.

During that two-year tour of duty in the Soviet Union, I had developed a taste for vodka — which became my painkiller and therapist of choice — an affinity that led to a series of less than stellar performance evaluations. After that disaster, I was exiled to Central and South American outposts where the Spanish I'd learned from my mother would come in handy and nothing I did would have serious policy implications for the U.S. government. My father's prolonged illness and my frequent trips out west to see him had made it impossible for me to take any more overseas assignments for the past six years. My career had been dying a slow and painful death in a series of dead-end positions at State Department headquarters in Washington.

"Continue," I replied, growing weary of Marty's little guessing game. "You really need this promotion, Angela." This conversation was becoming unbearable. I focused on my breathing, willing my anxiety not to resurface. "Marty, I'm going to hang up the phone right now if you don't tell me where the Department is sending me."

"Okay, you're going to Afghanistan in December." Oh, God, this has got to be a joke. I laid my head down on the desk blotter and closed my eyes.

-Excerpted from Farishta by Patricia McArdle. Copyright 2011 by Patricia McArdle. Excerpted by permission of Riverhead Hardcover.

Buying the book

You can purchase 'Farishta' at your local bookstore or online.

Articles in the media

- June, 2011: 'Farishta': Afghan Fiction From The Foreign Service - National Public Radio

- June 2011: Farishta: A Compelling Novel About War & Rebuilding, Love & Loss - Huffington Post